Back in the 1800s, medical care was such an inexact science that there was a real fear that you could be buried alive.

Newspapers in Europe and the United States published stories of people who had been wrongly buried after doctors couldn’t tell the difference between death and comas or trances. It was so common that Antoine Wiertz depicted supposedly dead cholera patients who had been buried in his painting “The Premature Burial,” pictured below.

Read More: During The Victorian Era, People Photographed The Dead (Yes, It’s Freaky)

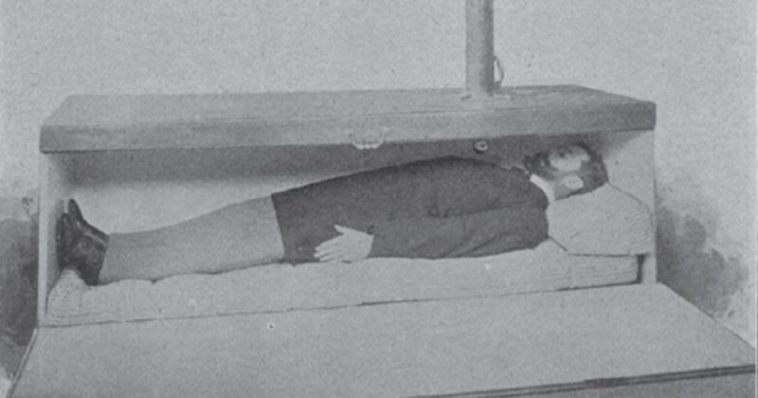

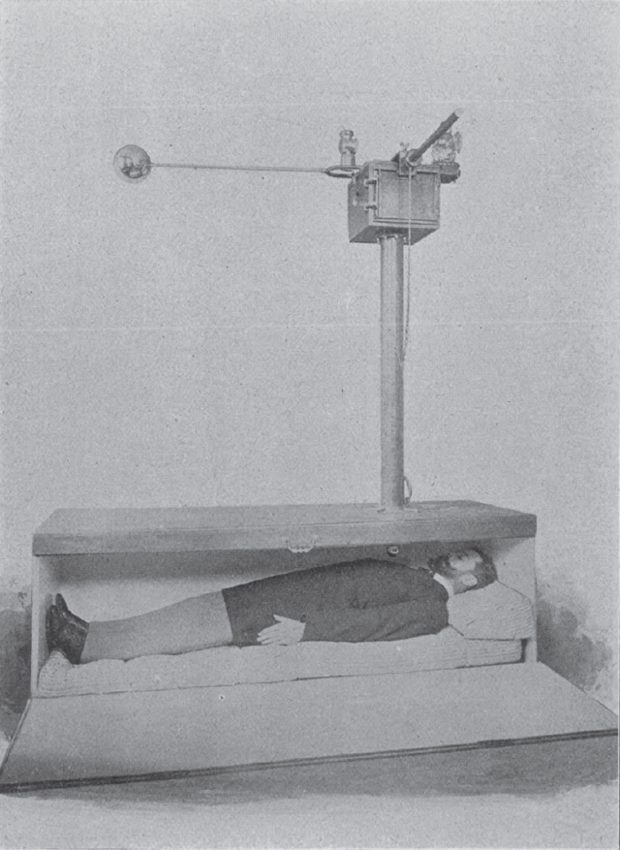

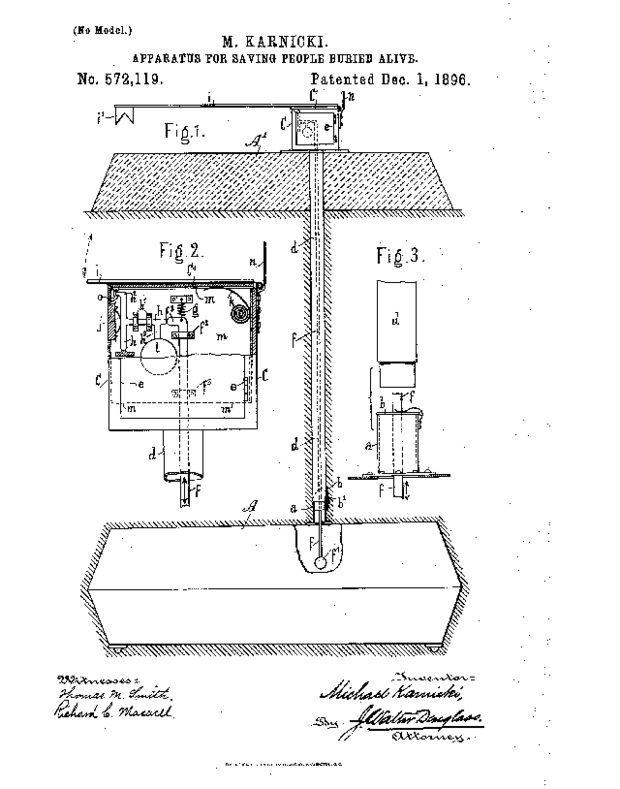

As fear spread, Count Michel de Karnice-Karnicki patented a special “safety coffin” with a variety of extra features intended to free people from six feet under.

The coffin was called Le Karnice, and it was set up to provide assistance to anyone who was buried alive, even if they were still in a trance. Full of literal bells and whistles to attract attention, along with spring-loaded release mechanisms triggered by movement, the Count’s coffin was the ultimate precaution against premature burial.

Due to its low cost and many layers of security, Le Karnice was an instant success.

The French Society of Hygiene recognized Karnice-Karnicki, and the London Association for the Prevention of Premature Burial endorsed his contraption. The top portion could be reused, which drove costs down, and grave diggers could build them fairly easily.

Read More: The Victorian Era Was Way More Morbid Than People Remember. Yikes.

Le Karnice fell out of favor when the coffin failed to work at a demonstration and medical professionals brought up concerns about decomposing bodies also triggering the springs.

(via MentalFloss)

The Count’s reputation never recovered, and despite his best efforts to spread interest to the United States, it did not gain traction. We did, however, get the phrase “saved by the bell” from the safety coffin phenomenon.

Comments